The Eyes Tell You The Truth

Date: 2023-2024

Medium: Animation,tuna eyes

Place: Eindhoven,the Netherlands

Exhibitions:

"DAE Graduation Show," Dutch Design Week, Eindhoven, 2024

"Bio Art & Design Award," MU Space, Eindhoven, 2024

Date: 2023-2024

Medium: Animation,tuna eyes

Place: Eindhoven,the Netherlands

Exhibitions:

"DAE Graduation Show," Dutch Design Week, Eindhoven, 2024

"Bio Art & Design Award," MU Space, Eindhoven, 2024

While geological surveys can unveil the age and origin of rocks and fossils, marine biologists can delineate the migration path of tuna by analysing the fish's eyes. In her investigation of the logistics of tuna imported to Japan, designer Zuika Owada uncovered deliberately concealed modern slavery within the East Asian tuna fishing industry.

In 2020, four Indonesian fishermen lost their lives on a Chinese tuna fleet in the South Pacific Ocean. Over more than a year, they had been treated as mere 'tools’ for catching tuna, stripped of their identities with no means of escape. Shockingly, 80% of the tuna they caught has been imported by Japan for the past two decades. Why has such a situation been hidden for so long?

This is where the economic, political, and social perspectives of Japan, China, and Indonesia intricately intertwine: Japan's surging demand for tuna, Indonesia's economic conditions, and China's political considerations concerning fishery resources. Building on this incident, Zuika Owada created an animation that raises questions about modern slavery and human rights abuses in the tuna industry, narrated through the eyes of a tuna.

Special Thanks:

Yota Harada (JAMSTEC, researcher), Shinichiro Ito (University of Tokyo, professor), Daiki Suda (University of Tokyo, master’s student), Mieke Meijer (Design Academy Eindhoven, professor), Basten Gokkon (Mongabay, journalist), Philip Jacobson (Mongabay, journalist), Environmental Justice Foundation (NGO).

In 2020, four Indonesian fishermen lost their lives on a Chinese tuna fleet in the South Pacific Ocean. Over more than a year, they had been treated as mere 'tools’ for catching tuna, stripped of their identities with no means of escape. Shockingly, 80% of the tuna they caught has been imported by Japan for the past two decades. Why has such a situation been hidden for so long?

This is where the economic, political, and social perspectives of Japan, China, and Indonesia intricately intertwine: Japan's surging demand for tuna, Indonesia's economic conditions, and China's political considerations concerning fishery resources. Building on this incident, Zuika Owada created an animation that raises questions about modern slavery and human rights abuses in the tuna industry, narrated through the eyes of a tuna.

Special Thanks:

Yota Harada (JAMSTEC, researcher), Shinichiro Ito (University of Tokyo, professor), Daiki Suda (University of Tokyo, master’s student), Mieke Meijer (Design Academy Eindhoven, professor), Basten Gokkon (Mongabay, journalist), Philip Jacobson (Mongabay, journalist), Environmental Justice Foundation (NGO).

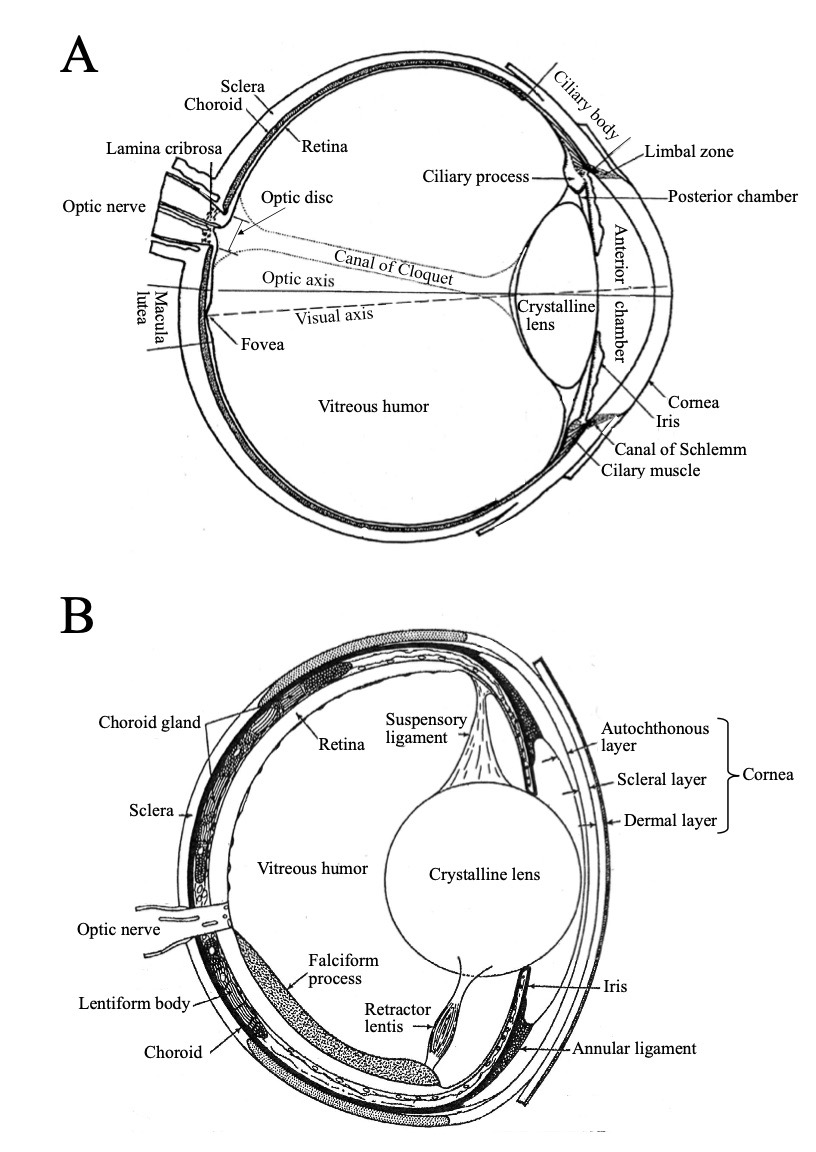

In 2022, a study by JAMSTEC[1], the University of Tokyo, and the Fisheries Research and Education Agency introduced a method to decode fish life histories using eye lenses. By analyzing nitrogen isotope ratios in the crystalline proteins of the lens via IRMS[2], researchers can trace the fish’s habitat distribution and feeding history. Combining this with traditional otolith analysis offers more precise reconstructions of migration routes. Since fish lenses grow in layers like tree rings, they preserve a lifelong record of growth and environmental data, crucial for sustainable fisheries management.

[1]Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology

[2] Isotope ratio mass spectrometer

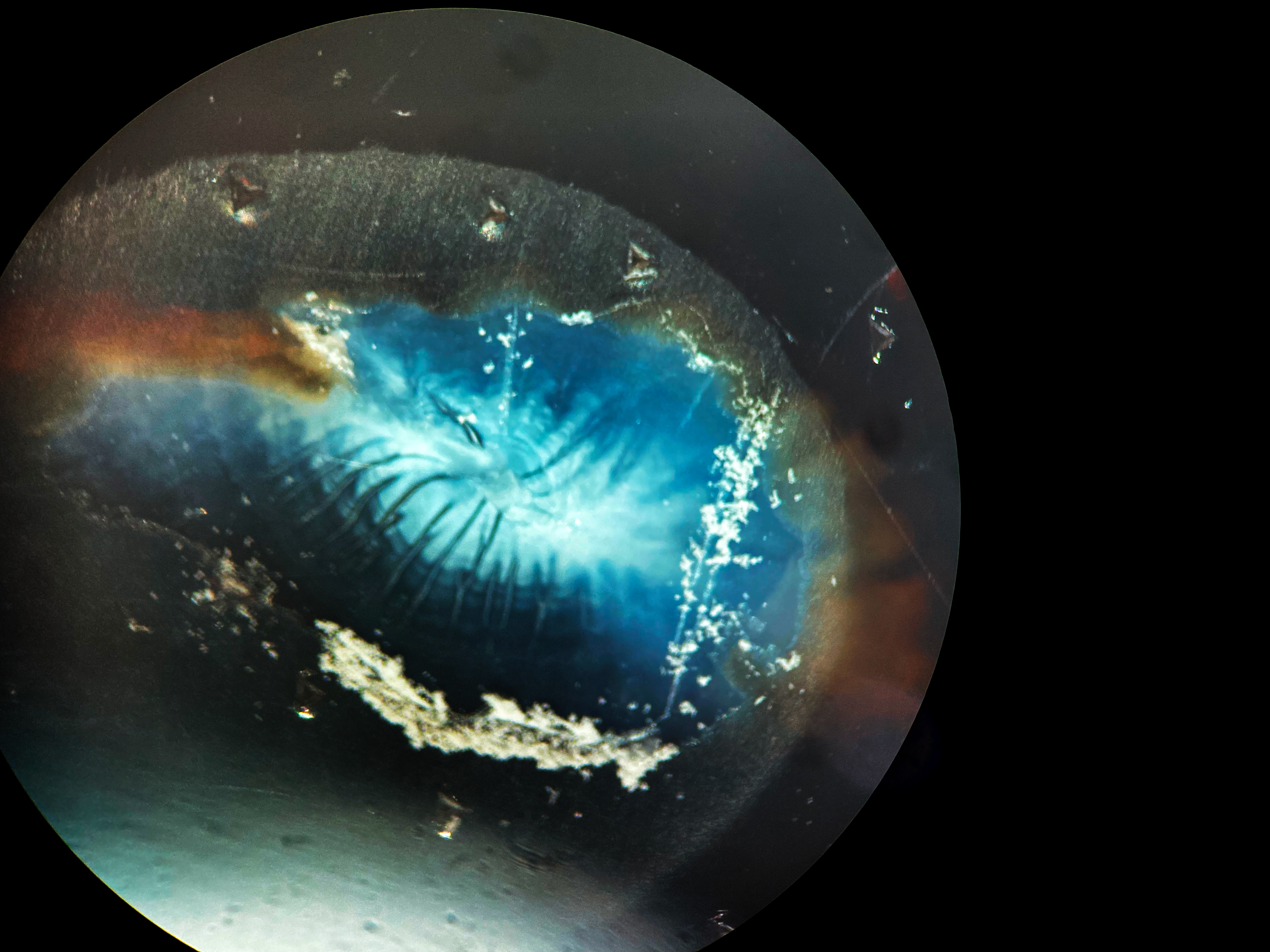

Zuika Owada collected and processed eye lenses from three types of tuna—bluefin, yellowfin, and bigeye. Despite differences in size, the number of rings in the lenses was similar. She used a special hardening process to create glass-like spherical objects from these lenses. Upon close observation, subtle ring patterns became visible, which were further enhanced by cracks formed during lens contraction. This resembles mineral inclusions[3], with layers storing various data. Over time, the lenss contract and transform into pearl-like white spheres.

[3]Inclusions such as different minerals or liquids incorporated into the mineral during or after growth

The details inside of tuna lens. Photo:Zuika Owada

JAMSTEC has developed equipment capable of measuring extremely minute nitrogen isotope ratios, enabling the analysis of compounds like amino acids at a molecular level. This technology has been applied to study fish ecologies, such as eel larvae diets and salmon migration routes, contributing to sustainable resource management. Additionally, it has potential for uncovering illegal fishing activities, including misreporting and labor rights violations, which are common in certain foreign vessels. These violations often lead to seafood products entering markets, including Japan, without transparency about their origins.

Advances in science and technology are enhancing our ability to trace fish migration routes and uncover illegal fishing practices. Zuika Owada discovered that some tuna import routes in Japan are opaque, leading to a significant revelation.

A report by the journalist collective Mongabay reveals that from 2000 to 2020, China’s Dalian Ocean Fishing (DOF), a major tuna supplier to Japan, was involved in illegal shark fin fishing and extensive labor abuse of migrant fishermen. These fishermen endured violence, were forced to consume rotten food and dirty water, and faced severe human rights violations. The harsh working conditions led to serious health risks, with many losing their lives as a result.

Mongabay’s investigation revealed that nearly all fishermen on DOF-owned boats reported being forced to work 18 hours a day, 7 days a week, sometimes enduring two consecutive days without rest during peak fishing periods. Despite these grueling conditions, many workers were unable to leave the vessels, which rarely docked, with some remaining at sea for over two years. This “transshipment” method isolated workers, limiting their mobility and increasing the risk of forced labor. Additionally, strict clauses in Indonesian fishermen’s contracts stipulated that failing to complete two years of service would result in losing most of their wages, with unpaid commissions to recruiters, creating significant debt collection threats in their home countries.

Photo:Environmental Justice Foundation

In recent years, a growing number of young Indonesians have become migrant fishermen abroad, leading to a surge in recruitment agencies in Jakarta. The number of these agencies has reportedly risen from a few dozen to around 600 in the past decade.

Japan’s purchase of tuna from the DOF was driven by a sharp decline in the number of Japanese pelagic tuna fishing vessels and the still high level of domestic tuna consumption; the number of Japanese pelagic tuna longliners, which numbered about 1,000 in the 1970s, declined to fewer than 200 by 2020.

The growth of China’s pelagic fishing industry is largely due to Chinese government policy: since the early 1980s, China has fostered the industry for food security and job creation, and in the early 2000s it incorporated it into its overseas expansion policy, encouraging companies to go abroad in search of new markets. Under this policy, China’s pelagic fishing industry received government fuel subsidies and expanded the size of its fleet.

Photo;Environmental Justice Foundation

Furthermore, in 2014, the DOF, with the support of Deutsche Bank, attempted to raise funds through an initial public offering (IPO) on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange to proceed with the purchase of longline fishing vessels. However, the plan was forced to halt after Greenpeace pointed out that the DOF had misrepresented the status of bigeye and yellowfin tuna stocks in a draft document it submitted, using outdated data to give the impression that the stocks were healthy.

This sequence of events highlights the opacity that exists in Japan’s procurement of tuna from the DOF, and suggests that forged documents and political agendas may have been involved in the transactions. In the past, the DOF had received assistance from American, Chinese, and Japanese wealthy individuals, but trust in the DOF has been shaken since the death of the Indonesian fisherman; in May 2020, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection took steps to ban all seafood imports from the DOF. In response, Japanese companies also stopped doing business with DOF after 2020.

In response to recent human rights violations in the fishing industry, Japan enacted the “Act on Proper Domestic Distribution of Specified Marine Animals and Plants” in 2020 to combat IUU (Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated) fishing. This law introduced a “catch certification system” for high-risk marine products and an “import management system” requiring exporting countries to provide detailed information. Additionally, over 50 countries have ratified the “Port State Measures Agreement” to prevent illegal fishing, with more expected to join.

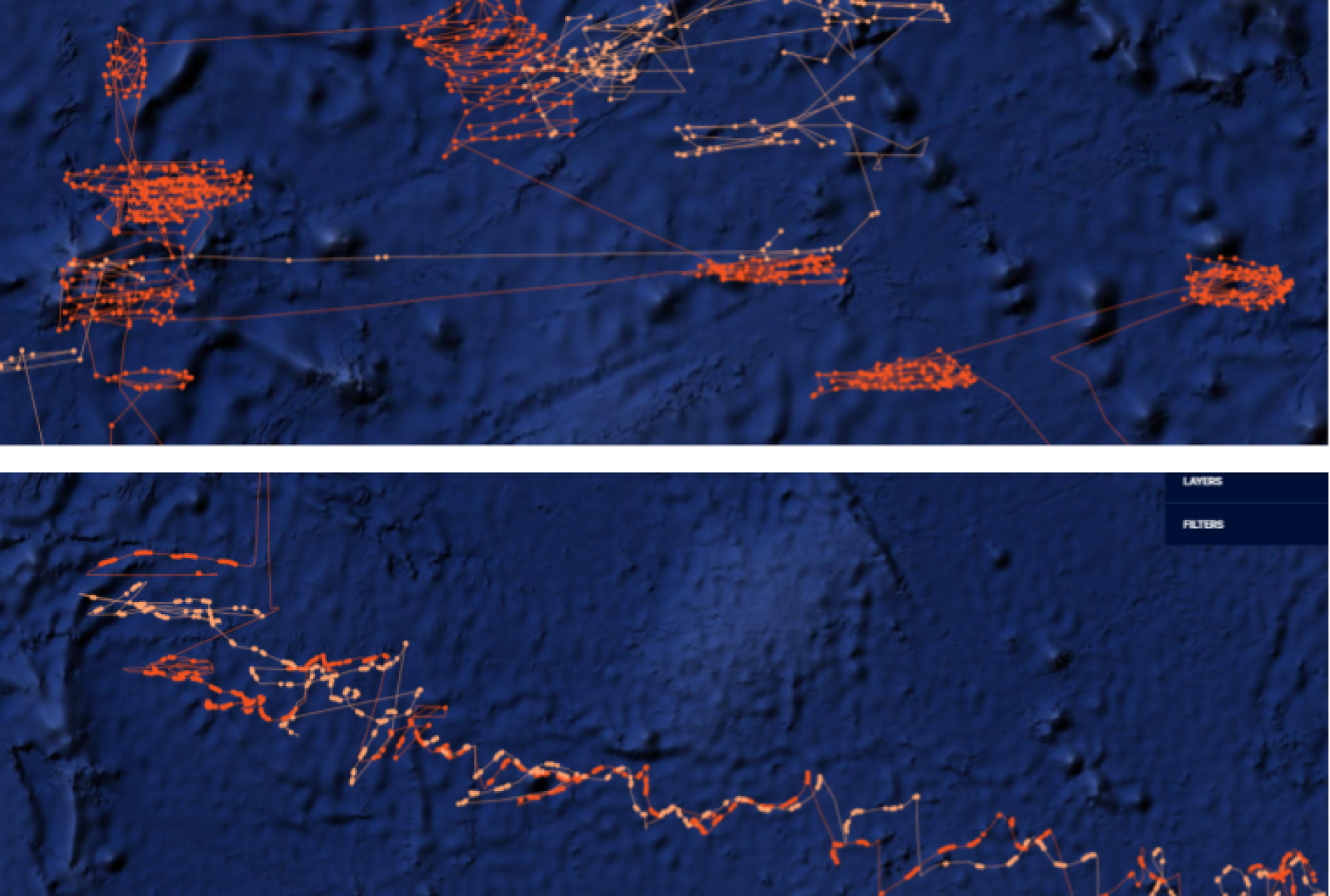

Photo:Mongabay, Global Fishing Watch

In May 2023, the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (SBMI) and Greenpeace Indonesia held a peaceful protest outside the Presidential Palace in Jakarta, urging the government to expedite the approval of regulations to protect Indonesian migrant fishers. In response, the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs intensified efforts to strengthen regulations, focusing on protecting not only Indonesian fishers but also those from other Southeast Asian countries. These regulatory enhancements are vital for sustainable fisheries and safeguarding workers’ rights through international cooperation.

To promote transparency in the fishing industry, Google has also developed Global Fishing Watch (GFW) in collaboration with Oceana, which works to protect fishery resources, and environmental group SkyTruth. The tool’s mission is to promote sustainability in the world’s oceans by providing visibility into global marine fishing activities.

The data and analysis results are provided to researchers, governments, and NGOs, and an interactive map of all vessels’ locations and trajectories is available on the GFW website. This system has dramatically improved the transparency of fishing activities and enhanced monitoring of IUU fishing. Several fisheries companies are already using the GFW to provide buyers with tracking information on fishing vessels, and it is hoped that one day in the future consumers will be able to see which vessels operated where simply by scanning the barcodes on the packaging of seafood products.

Other organizations working to end IUU fishing include the Regional Fishery Body, EJF, the Southern Bluefin Tuna Conservation Commission, Seafood Legacy, WWF, and GFTC. These organizations are working together on a global scale to eradicate illegal fishing and protect the rights of workers through stronger international regulations and on-the-ground monitoring activities.

Zuika Owada revealed that tuna import routes to Japan are often opaque, with Mongabay exposing China's Dalian Ocean Fishing (DOF) as a major supplier involved in illegal shark finning and labor abuses from 2000-2020. Migrant fishermen faced severe human rights violations, working under extreme conditions. DOF's deceptive practices led to an international ban, and Japan responded with stricter regulations on marine imports to combat IUU (Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated) fishing.

Photo:GreenPeace East Asia, Indonesia

In Japan, investigative groups like Tansa and the Minami-Nippon Shimbun reported on labor issues within the DOF. In response, the government has strengthened efforts to crack down on illegal and unreported fishing and is working to establish a traceability system for seafood. Companies are also developing and implementing seafood procurement standards.

I extracted key phrases from related articles, creating illustrations that depict these issues, such as severed ankles symbolizing workers trapped on ships, and linked them to crystal research at the University of Tokyo. These illustrations were compiled into a two-minute frame animation, evoking a haunting message.

The animation begins with a tuna on a cutting board, with the perspective then diving into the tuna’s eye. Initially, it seems to tell a brutal story from the tuna’s point of view, but it gradually shifts focus to the workers. Across 1,800 frames, repetitive sequences depict the laborers’ monotonous daily lives, revealing the hidden truths of the tuna industry. The animation uses real fishing boat sounds to enhance its realism, making the experience more immersive and impactful.

The project was also published as a research book, offering deeper insight into the scientific findings, fieldwork, and social contexts behind the work.